The Shipping Dead

Will drones really save shipping?

Authored by Martin Leduc

May 25, 2015

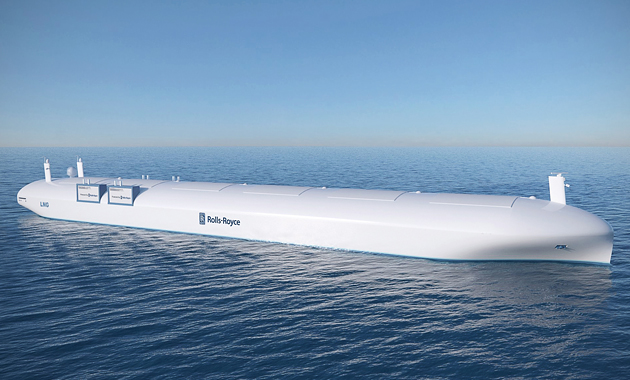

We�ve been hearing a lot about drone ships this past year, and how soon they could be utilized by shipping companies. Drones have proven effective by the military, to kill people anonymously, from a safe distance - a machine that allows humans to remove their soul from their actions. The long-term dream of many shipping companies is to get rid of that scourge on their balance sheets, polluting their profits, the dreaded human crew. Drone ships finally offer this possibility and the technology the military has demonstrated, puts this in the realm of possibilities in the near future.

I thought it would be interesting to think about what a drone ships might

need to operate, and if really there would be any savings. After this exercise,

I would venture to say that, no, there would be no savings. The people needed,

would just be needed ashore, to tend to more complex systems which would require

a higher caliber of specialist training. Not to mention a high degree of redundant

technology and solid equipment onboard and ashore, that would undoubtedly cost a

premium.

"Circle Jerk" in the Aleutians

It was Thursday morning, 6 am, the holographic alarm clock flashed videos and

sounds of the grandkids, always letting me wake up with a smile. In the

bathroom, shaving, I could see the extensive list of message in the discussion

box, flashing on my mirror; it had been a busy night at the company's control

center, Hope Center.

It was Thursday morning, 6 am, the holographic alarm clock flashed videos and

sounds of the grandkids, always letting me wake up with a smile. In the

bathroom, shaving, I could see the extensive list of message in the discussion

box, flashing on my mirror; it had been a busy night at the company's control

center, Hope Center.

Located in the Vancouver suburb of Hope, nestled in the mountain's bedrock, the seismically enhanced warehouse had been recently converted into a massive marine transport drone control center, one of six around the world. The company had bought in, big time, to the whole idea of drone shipping, but after 15 years of successes and misses, the jury was still out on drone ships.

The technology on paper was a simple proposition. The communication infrastructure needed was massive, the center was actually on the third floor of the warehouse, the bottom two floors held countless banks of electronic equipment, tended to by an army of engineers and computer whizzes. Communication between the centers and the remote ship was paramount.

Sprawling Vancouver was now part of Cascadia, the pacific northwest grew tired of the constant need to deplete its resources, so they had seceded from Canada and the USA to form its own country, Cascadia. Cascadia was a poor country, compared to its South American and Asian counterparts, still developing, dealing with massive immigration issues, and poor infrastructure.

Cascadia had one thing going for it, it had embraced tidal and wave energy which provided a reasonably stable electrical grid, so it was far ahead of its impoverished neighbors to the south and east. The company had established here because of that - reliable power, nevertheless, still had to maintain huge battery banks and gas generators, as any loss of power would create chaos in the supply chain.

In our world, power was everything, not the greed type power, but electricity. Bulk drone 4598, also known as Bellagosi, seemed to have lost power and lost signal with its operator in a sister control center, located in Morocco. The 20,000 tons vessel was loaded with a synthetic quinoa, on a World Food program delivery from Siberia to what use to be Los Angeles. A hungry populace is a breeding ground for instability, the cargo, like all cargo, was needed right away.

The company's headquarter in Egypt, transferred responsibility for the Bellagosi to Vancouver; it was now our responsibility to figure out what happened and get it fixed, quickly. By the time I arrived in the office, the vessel had suffered numerous issues as far as we could tell.

It was still broadcasting rudimentary information, position speed, emergency conditions, and such, to the satellites, but it was not in real time. Bellagosi had gone into a default mode, fail safe mode, doing circles off the Aleutians islands. Because it was the lead ship of the convoy of four, they had all "defaulted", or as we liked to call it in the workshop, they were in a "circle jerk"; but then again, that was a popular descriptive in the company.

Hope Center

Everyday day of the year, four operators took turns supervising the convoys,

monitoring the progress and

each of the vessel's systems. They would sit in one of the six control stations

on the upper floor, every two station would have a supervisor station and an

assistant. Together they could control up to six drone ships at time, leading

convoys of up to six units.

Everyday day of the year, four operators took turns supervising the convoys,

monitoring the progress and

each of the vessel's systems. They would sit in one of the six control stations

on the upper floor, every two station would have a supervisor station and an

assistant. Together they could control up to six drone ships at time, leading

convoys of up to six units.

The operator who had inherited the mess - Bellagosi, and the other three drones - was James "Jam" Rouen. As I pulled the hover bike over the recharge spot at the center, Jam was busy trying to figure out what the Morocco operator failed to see, that led to the "circle jerk" in the Aleutians.

"Jam" as he was known in the center was a smart kid, known for getting us in, and sometimes out of jams, was fresh out of formation. Formation was a four week introduction to ships, but mostly to the electronics that control them, the communication system that banded them all. These young guys were chosen by aptitude test as to who was the best video game player, that was the number one hiring criteria - as long as we had lots of Tesla Energy drinks around, they loved their jobs.

It was mostly an automated process, but once in a while, an issue would creep up. A ballast pump seal would blow, flooding a compartment causing an alarm, the automated system would isolate the system automatically, but that was only in a perfect world, where the sensor were properly working, and the back-up system was hopefully in better shape than the primary one.

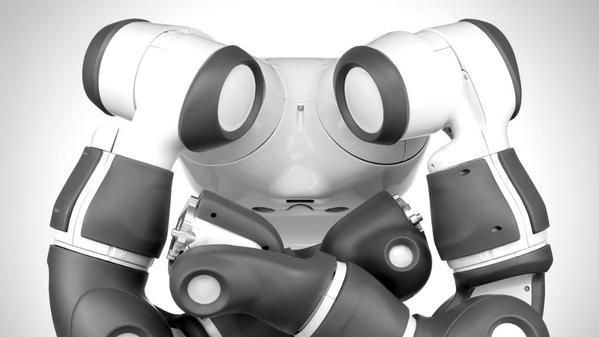

The company had recently installed rudimentary robots which were able to navigate the vessels confined passageways which allowed remote visual inspections of equipment. We called the robots "Oilers", after an old term for an engine room assistant. These proved valuable in getting a clearer picture of the issues, and it saved us time, but ultimately they were limited in use since they only had one simple function "arm". Computers and gadgets are good, but there is still no match for the human capabilities and versatility.

"Super" takes on new meaning

When the company needs versatility, they still call on the humans.

I am one of the Technical Services Supervisors at Hope Center, from the "old

school" some say, and I actually use to sail; feels like an eternity ago. My

boss is a young Electrical Engineer who worked at the now defunct SpaceX, he's

from Turkmenistan, he's got a great ability to talk in circles. They keep us old

guys around in case talking does not resolve anything; needless to say I am

overwhelmed with issues that need to be address, "yesterday".

When the company needs versatility, they still call on the humans.

I am one of the Technical Services Supervisors at Hope Center, from the "old

school" some say, and I actually use to sail; feels like an eternity ago. My

boss is a young Electrical Engineer who worked at the now defunct SpaceX, he's

from Turkmenistan, he's got a great ability to talk in circles. They keep us old

guys around in case talking does not resolve anything; needless to say I am

overwhelmed with issues that need to be address, "yesterday".

I have a title, Technical Superintendent, and I am expected to go from one problem to the next, provide suggestion for a solution and guidance to the technicians that will execute the plan of action. The company grudgingly accepts our plain spoken ways, and hates most of our solutions. One thing that had not changed from the past, companies still hated our "engineers' lineage, always costing them money, or so it's seemed, to the accountants.

I stopped briefly in my office, at the back of the workshop, where I marshaled my �forces�. Today�s designated Technical Response Unit (TRU) was made up of Terry, the hulking Irishman, a go to guy for electronics, Justin, 1.5 meter tall, was called �The Big Unit� and the guy with the mechanic skills, he could troubleshoot a fuel generator system like no one, not to mention could fit in some very tight spots. We had a lackey, Cory �Sparky�, a sort of guy you could never get rid of due to his shear eagerness, or maybe due to his puppy dog bad luck. Sparky had an ability to survive anything, but strangely not the ability to prevent them, he was the team�s "gofer guy" - go for this, go for that.

They were meddling about in the workshop at the back of the Center, I gave them a brief intro of what I'd heard. "Four drones circle jerkin' in the Aleutians, get your flight bags ready". We all knew we were in for a very long day.

I headed past the endless offices full of Managers, Directors, Executives, I'm not sure exactly what they all did, but they all had the fanciest hover-rides, wore the latest metrosexual outfits, and permanent fake after five shadows, a re-emerging fad that the world could do without.

Jam was in video-teleconference with Morocco in the Fleet Super�s cubicles, the Fleet Manager, and the Director of Operations was already there, along with some no names bodies, holding clipboards close to their chest, perhaps guarding highly prized possessions, maybe last night's winning lottery ticket - a two room dwelling unit in Mission.

The jest of it was that the operator in Morocco reported trouble maintaining speed, and reported several ingress of water alarms. Then suddenly the video and data stream stopped, and the back-up communication array could not maintain the bandwidth capability with the satellite. The Bellagosi went in default mode, along with the rest of the convoy. Simple enough, really, it did what it was suppose to in case of problems, that's a good sign, I thought to myself.

They looked over the data, and did it over again. They had re-tasked a satellite to "hover" over the vessels. There was some good news; the vessels were there, doing circles in the Alaskan Gulf at thee knots, flashing their "not under command" lights. I think I could see why the communication was down, the forward mast was not where it was supposed to be. We were getting telemetry from inside; there was no fire, no major flooding, the cargo was still intact; more good signs.

With all this technology and formation, the operator could not read a weather forecast. It's the Gulf of Alaska, it's December 10th, there is a high probability that weather was pretty damn inhospitable, like it's been there for millennia's. Back in the day when we had crews onboard even the thickness of Mates would have altered course to prevent damage to the ship. In fairness to the Operator in Morocco, who now feared for his job, the accelerometers should have picked up the excessive forces and should have warned him, but for whatever the reason, the system failed.

The Director of Operations looked to me and asked what I thought, but he already knew what needed to be done. A crew would have to board the vessel and inspect the damages, rectify it, and move on. Its a simple plan, really, just the execution of it gets complicated.

On the way to the workshop I called my partner, told her not to expect me tonight, she'd have to watch Ninja Crochet on the holotube by herself. She laughed, she knew I hated that show, but every Thursday night, it was her thing, humans have been doing these stupid rituals for centuries. I was going to brief the team, but they had done this a thousand times, they knew the drill, and were already prepped to go.

Send in the Vulture

The company maintained several aircraft at the ready for this type of occasion,

although most of the aircraft were used for "corporate" travel. However, not many

corporate types liked our "Vultures" as we called them. Grimy, dirty, oily,

flying toolboxes with tight uncomfortable seats that reminded you of them, long

after you finished the job. These Vertical Take Off and Landing (VTOL) aircrafts

were called Vulture because they only came out when something was dead or dying.

The company maintained several aircraft at the ready for this type of occasion,

although most of the aircraft were used for "corporate" travel. However, not many

corporate types liked our "Vultures" as we called them. Grimy, dirty, oily,

flying toolboxes with tight uncomfortable seats that reminded you of them, long

after you finished the job. These Vertical Take Off and Landing (VTOL) aircrafts

were called Vulture because they only came out when something was dead or dying.

The company had gotten a "great deal" on these from the military; each costing roughly C$70 million a piece. Back in the day, these Vultures were known as Ospreys. The military had spent endless amounts of amount of capital, and numerous lives were lost in crashes during their development. Now, the company needed the speed to get to a ship at sea, but still needed to land on it. A plane had the speed, but the helicopter could land on a dime, the Vulture became the best of both worlds, and, as a bonus, they had worked out most of the bugs that caused them to crash. These were old but still pretty tough, I respected them, like I respected a Doberman.

Once off the ground, it took about 4 hours to get to Kodiak, we refueled and stretched our legs, before continuing on to the Belagossi and its mates. The convoy was bobbing in the ocean, 120 miles south from Unalaska, in the Gulf of Alaska. During the flight I had time to catch up on my seemingly endless "paperwork" and reports. I also had a look at the maintenance history of the Bellagossi, and briefed the legal department by video conference. We had better be prepared to deflect blame, as the charterer will surely find a way to get out of paying for the whole trip at the first opportunity. I'm sure the company was already on their knees to smooth things over, afraid to lose a contract. The minor players like the Murmansk Maersk Company were always snapping at our heels, so it was important to save face as quickly as possible.

The maintenance database listed several complaints about the accelerometers and their unusual response. This raised some red flags to me, and may have been why the operator wasn't warned of the forces acting on the vessel. At the Bellagosi's last maintenance period in the Galapagos Shipyards, this service item was deemed a low priority, as it had tested good during self checks; maybe this was a bad decision.

By the time we overflew the Bellagossi, and its companions, nothing had changed to any great degree, the weather had improved somewhat. While we surveyed them from the air, Justin, was setting up local communications with the Bellagossi in an attempt to navigate into the wind and make our landing a bit safer. Landing such a big aircraft on a small ship, was a risky operation at the best of times, especially since the Bellagosi pitched and yawed considerably in these Alaskan waters. Not having any success, in bringing up navigational control, we checked in with the Hope Center for the okay to do a risky, hot landing.

Risks, what risks, really the most important risk to consider was to the bottom line, so of course they were going to tell us to go ahead despite the wildly pitching decks below. We had to go through the checklist, and get approval as a formality. The Vulture pilots were well verse in these, having done them with some unhealthy regularity. Hovering over the pitching Bellagossi number three hatch, the only topside spot to land, the pilots lowered a cable into the "bear trap", which reeled the aircraft down tightly to the deck.

The weather was great, for Alaska, blowing 35 knots from the Northwest, rain mixed with snow, swells of 4-6 meters, a beautiful day to be out on the water. Removing crews from ships was a sad thing, but probably one of the healthiest thing to do for them.

Carbon fiber mess

Terry and I made our way forward where we had seen most of the damage from the satelites, walking along the side of the vessel was treacherous, and we clipped ourselves to the lifeline. Justin and Sparky proceeded aft, to the propulsion room to check things out.

The forward mast was a robust unit, fortunately it was made out of carbon composite, it was light, maybe eight feet tall, but still manage to shear its mounting bolts off, it looked like they were the wrong type of bolt and had most likely corroded beyond their working strength. Because the company wanted to maximize the power output of the solar panel, and increase the capacity of the holds, they had chosen to place the forward mast near the bow, quite exposed in my view. A wave probably came up over the bow and try to snatch the mast away. Fortunately, we had not lost it overboard, like so many times before.

The forward mast held the forward navigation light, a slew of cameras, weather instruments, and built into the back of the mast, the main satellite dome, about 2 by 2 foot wide ball, housing the dish.

Part of the mast had fallen on the power collector box for the massive solar arrays that were the cargo hatch covers. It had not damaged the actual array, but some of the wiring's insulation was torn off, and several wires were crushed. Terry quickly traced the problem of the secondary communication failure to a blown, well, fried, circuit board at the forward control locker. Probably caused by the power spike when the mast hit the connection box.

We had our hands full and it would take quite a bit of time to resolve this, and in these conditions, it would would be tough grueling work. The Vulture pilots tended to the general safety of the operation, made meals onboard the aircraft, kept in contact with center, answering their mundane questions.

Terry and I proceeded to fill out the Job Safety Analysis, prompted by our retinal displays that double as our safety glasses. Video linked to my supervisor ashore, we discussed what needed to be done, and how we would proceed with it. The program automatically listed the steps as we described, which was a handy reference, that kept both Terry and I on pace.

The mast was not particularly damaged, and weighed about 1200 kilos. It had simply rip off cleanly at the base, and had jam itself against the hatch cover, so most of the wiring could be salvaged. Terry would complete the rest of the wiring, which really wasn't complicated - a fiber optic cable and some power cables.

In order to right the mast and reinstalled it, we needed some help. We had Justin and Sparky come back up to assist with the bolts while Terry and I donned the MuscoSuitsLt; a hydraulic powered suit that amplified the strength of the human body. It provides great force in doing work with near full range of human motion, yet be tactile enough to do precise work. Really, a marvel of engineering. The Vultures each had two onboard, which made moving heavy parts around the vessel a far less risky task than it used to be.

However working with the MuscoSuits on the forward, open decks was worrisome, so Justin remotely re-tasked the three other drone vessels alongside, to provide the greatest possible lee, and altered the convoy's course to facilitate a safe as possible operation.

With all hands on deck, Terry and I in our MuscoSuits performed a tandem lift of

the mast, carefully guiding it over the mounting flanges. Sparky and Justin, spud

wrench in hand, lined up the holes and began to place new bolts back on. Once

completed, the tedious task of reconnecting the wiring harnesses was at hand.

While the team tackled the wiring I started to investigate the burnt out circuit board. Using the Retinal Display I searched the ships database for a spare board, and of course, there was none onboard, and none in the Vulture either. I contacted Switzerland, home of the system designers, and spoke with a service technician, showed him the issues and we both agreed it would need to be replaced.

Over the network, he sent over the part plans, which had been improved somewhat from the original - a multilayered printed circuit board. It was more compact, but created some issues in the field. In the Vulture, I loaded the proper stock in the 3-D printer and loaded the program with the files Switzerland provided. It would take about one hour to print out the multiple layers and I would let Terry finish the assembly. On the smaller 3-D printer, I printed off various connectors and piece that had been found to be broken.

The crew was pretty tired by now, so we rested in the Vulture, since the Bellagossi had no creature comforts, not even a toilet. The Vulture was crammed pack with all the gear we needed, somehow we had managed to fit a toilet in there too, we didn't have to resort to the old bucket and string thing. The pilots had warmed up some ready to eat meals; not the best, but it was nourishing. The coffee taste like turpentine, but the warmth it provided was quite welcomed. I always wanted the crew to take a nap so as to prevent any stupid mistakes, so we call it quits for two hours. I always get an earful from the Supervisor, but he�s not out here working in the elements for hours on end. Fatigue catches up to you real fast, even if you�re making double time wages, and danger bonus.

A great idea... in a perfect world

The 3D printers had completed their tasks, and after our rest, Sparky and

Terry carried on with their rewiring. The weather had lightened up a bit which

was quite welcomed. Justin and I proceeded to propulsion compartments to check

out some of the other issues that had been logged as defiencies by the Control

Center operators.

The 3D printers had completed their tasks, and after our rest, Sparky and

Terry carried on with their rewiring. The weather had lightened up a bit which

was quite welcomed. Justin and I proceeded to propulsion compartments to check

out some of the other issues that had been logged as defiencies by the Control

Center operators.

First up was the central cooling system suction. The automatic SW strainer back flush was functioning and the strainers were clean, but the pump just didn't seem like it was moving any water. We took apart what we could but traced the problem to the sea-bay itself. Judging from the previous port of call in Bangladesh, I figured the suction valve or piping was clogged with plastic garbage, a frequent occurrence in that part of the world. I schedule a diver for the next port of call; the back up pump and sea bay would have to hold unto then. We could have sent down the Remotely Operated Vehicle to see what was happening, but in these open waters, we could lose it too easily to current.

Next was the back-up communication located in the rear mast. Everything seemed to be working well but could only establish weak and intermittent contact with Hope Control. After an hour of searching we finally found that an improperly stowed oil bucket had come loose, struck the control cabinet for the antenna tracking system. The shock shut down the logic for whatever reason; a simple power down and reboot was required, and within 30 minutes the antenna was tracking the satellite correctly.

Justin had checked on the gas generators, which broke down seawater into useable hydrogen to feed the fuel cells. Three generators sat in two containers, which could be swapped out in port, similar to a large battery. The plants provided the bulk of the power needed to drive the two five mega-Watt thrusters. Justin had run a diagnostic on the battery banks, and had attempted to rectify the two issues identified, hotspots on the connection. Not unusual, but we could not take care of it in the field, so yet another item for later.

The Bellagossi, would need some down time for some extensive maintenance soon. They would need to swap out the battery pack send it ashore and get it serviced by the OEM, these packs had not lived up to the company�s expectations, lasting only 5 years instead of the 8 years advertised.

We then had a look for the accelerometers; the cabinet they were housed in had the door gasket misplaced, most likely from the last checks. That had allowed sea air to corrode the contactors of the unit, giving a weaker signal than normal. We could visually see why the unit was giving wrong information, it wasn�t making proper contact. Luckily the vessel had a spare so we chose to replace the entire thing out, why risk another accident.

The team was getting quite tired, so I decided to call the mission. With the testing completed, both communication systems back up and running, we had accomplished what needed to be done, and more. Hope Center was happy to have the Bellagossi and the rest of the convoy back. We cleaned up our tools and equipment, and before even closing the rear door, the guys were fast asleep in their seats, exhausted; I soon joined them, while the Vulture hurtled through the brisk Alaskan air.

After a very long days away, we would get two days off, on top of the double pay, and the danger premium this mission represented. Another TRU was waiting for the Vulture as we arrived back at the Pitt Meadows Air and Space Port. The operator of 2347 had ventured close to land, where a land based hacker had used a brute force hack, and gotten into the navigation system of one of the convoy drones. The system was robust, and the hacker did not succeed in stealing this vessel, but being compromised, the company did not want to take chances, and had tasked the TRU to physically swap out the hacked brain box out, and try to determine the person responsible once it was back on land.

All in a days work.

![]()